The Colorado River’s flow has declined nearly 20% this century under the pressure of a changing climate. Three of the four Upper Basin states are already overusing their rights to the river, and that water deficit will grow significantly as snowpacks continue to diminish and the river is reduced further.

After a year of careful research, we have published a report on the repercussions of this overuse, the dire predictions for the future, and what it means for the Basin’s human and non-human residents.

Rising air temperatures mean we need to prepare now for a future with less water in Utah’s rivers.

It is undeniable that Utah’s temperatures have risen dramatically over the last 30+ years. This temperature increase is an existential threat to Utah’s watersheds and will have major economic impacts on every Utah resident. We stand at a crossroads — we can continue to ignore the effects of the changing climate or we can adapt to our new reality.

How warm will Utah get?

It has been estimated that by 2050, air temperatures in Utah will be about 3°F higher in winter and about 3.6°F higher in the summer compared to current temperatures. By the year 2100, average Utah air temperatures may increase by about 6°F in winter and up to 8°F in summer above today’s temperatures. The effects of such drastic temperature increases could be catastrophic—especially if we ignore the issue.

What does a three degree increase in temperature mean for Utah?

Less Snow

Over 80% of the Wasatch Front’s water comes from snowmelt runoff. Utah’s hydrogeologic system depends on a healthy snowpack to hold water and prevent loss through runoff. Increasing air temperatures will result in more rain and less snow in the mountains. This, in turn, threatens our snowpack and will diminish spring and summer run off which will have massive consequences on our ecosystems and economy.

Climate models indicate there may be a 5-15% increase in precipitation levels in Northern Utah, but rising temperatures mean this will occur more frequently as rain—leading to less snow accumulation and an earlier snowmelt. Because the snowpack is instrumental in holding water long into the summer months and preventing water loss through runoff, less total snow and earlier snow melting will likely lead to droughts and water shortages happening on a frequent basis.

As air temperatures have increased due to climate change, a diminishing mountain snowpack and changing precipitation patterns are already reducing flows in the Colorado River. As this warming trends continues, the flows of the Colorado River are predicted to decline as much as 20-30% by mid-century, impacting 40+ million people’s water supply.

The Colorado River Compact divides the flows of the river among the 7 U.S. states, Mexico and Indian Tribes based on a total of 16.5 million acre-ft. But the 30 year average shows that there is actually just 11 million acre-ft of water in the river, and this average is continuing to decline as air temperature increases. Simply put, there isn’t enough water in the Colorado to go around.

Megadrought

While a few degrees of warming may not sound alarming, we are already seeing the profound impacts of a warmer, drier climate across the west. A climate study published in Science coined the term “megadrought” to describe a multi-decadal drought. The findings highlight that the Southwest has not been this dry since Leonardo da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa, roughly 500 years ago. One of the Colorado River Basin’s foremost climate scientists on water availability, Dr. Brad Udall estimates that we can expect the Colorado River Flows of the 21st century to be 20-30% lower than what was observed in the 20th Century.

This historic Megadrought is already fundamentally altering the hydrogeology of the American Southwest. Reservoir levels and river flows are plummeting, causing, for the first time in the history of the Colorado River Compact, other states to take mandatory cuts to their water supplies.

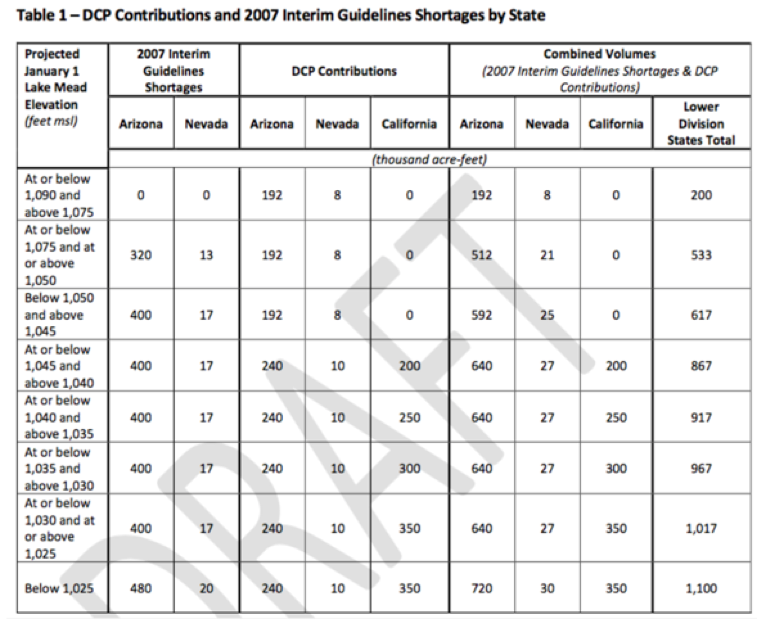

These mandated cuts are a part of the Colorado River’s lower basin states Drought Contingency Plan (DCP). The DCP is a basin wide agreement that uses the water level of Lake Mead on January 1st of every year, as a gauge to ensure that the Colorado River is not over allocated. When Lake Mead falls below an elevation of 1,090 ft, lower basin states are mandated to cut their water use allocations from the Colorado River. Larger cuts are triggered at lower elevations, that include all lower basin states.

Lake Mead is nearly 10 ft below the threshold for the DCP, forcing for the second time in history, mandatory cuts to lower basin states water supplies. Consequently, Arizona must give up 192,000 acre-ft of water, Nevada must cut 8,000 acre-ft, and Mexico must cut 40,000 acre-ft from their supply. Lake Mead will likely fall below the next elevation level. in elevation, triggering deeper cuts of 512,000 acre-ft, of 1,075 ft21,000 acre-ft, 50,000 acre-ft from Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico respectively.

The new reality is states are taking cuts to their water supply and are being forced to adapt to the changing hydrology of the Colorado River, and Utah continues to ignore reality by seeking expand its water supply, while having the highest water use per person in the country. When will the Upper Colorado River Basin States, which includes Utah, face mandatory cuts, rather than continuing to develop allocations that no longer exist?

Chart from the Bureau of Reclamation highlighting the severecuts States will need to make to Colorado River water use as flows continue to decline.

Its time to act!!!

Utah is the second most arid state in the nation, and as temperatures increase, we can expect less snow at the end of each winter, with runoff occurring at a faster pace. If Utah water suppliers are serious about climate change, they need to get their act together. They are decades behind other water suppliers in the west when it comes to water conservation and they are even further behind when it comes to climate adaptability planning. These agencies need to estimate how much less water they will receive in coming years as a function of climate change, and develop plans to mitigate the impacts while adjusting to our megadrought reality.